Economic crime research strategy: Home Office research priorities

Published 4 May 2021

1. Foreword

Economic crime is a unique threat that impacts:

- national security, underpinning serious and organised crime and posing an international threat through corrupt elites linked to hostile states exploiting the UK’s financial systems

- prosperity and economic resilience where in an increasingly digitised economy, online volume fraud poses a direct threat to the UK’s post-COVID economic recovery

- the UK’s global reputation and influence as a stable, well-regulated economy, which is vital to attract and maintain investment

Economic crime refers to a broad category of activity involving money, finance or assets, the purpose of which is to unlawfully obtain a profit or advantage for the perpetrator or cause loss to others. It includes criminal activity that:

- allows criminals to benefit from the proceeds of their crimes or fund further criminality

- damages the UK’s financial system and harms the interests of legitimate business

- undermines the integrity of the UK’s position as an international financial centre

- poses a risk to the UK’s prosperity, national security and reputation

Fraud is estimated to be the most common crime type in England and Wales, with nearly every individual, organisation and type of business vulnerable to fraudsters.

The laundering of proceeds of crime is a key enabler of most serious and organised crime impacting the UK.

Bribery and corruption undermine fair competition and are barriers to economic growth, especially in the developing world. The threat is also continuously evolving, impacted by the emergence of new technologies, services and products such as crypto-assets.

To ensure the integrity of the UK’s financial system, protect our vulnerable people and communities, and attract business to the UK, we must do all in our power to combat economic crime.

The Government’s Economic Crime Plan 2019 to 2022[footnote 1] published in July 2019 sets out 52 actions that will improve the UK’s response to economic crime. This document relates to Action 5 to: “‘Resolve evidence gaps through a long-term research strategy’: Home Office, with support of National Economic Crime Centre (NECC), HM Treasury (HMT), Ministry of Justice (MOJ)”.

This Economic Crime Research Strategy represents a development in the UK’s response to economic crime and will lead our future response to this threat. It builds on the commitments made in the UK’s 2016 Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Action Plan, 2017 Anti-Corruption Strategy, 2018 Serious and Organised Crime Strategy, and 2019 Economic Crime Plan to provide a collective articulation of the action being taken by the public and private sectors to ensure that the UK cannot be abused by economic crime.

An important part of building the UK’s capacity to respond to economic crime is in improving our evidence base. Good quality and robust research will allow a comprehensive understanding of the threat and the most effective and efficient use of resources.

The ever-evolving and clandestine nature of economic crime means that it can only be combatted by harnessing the capabilities, resources, and experience of both the public and private sectors. Therefore, the Home Office, working with key partners, has produced a long-term research strategy, setting out the key evidence gaps in our understanding of the threat from economic crime.

The aims of the research strategy are to:

- map existing work that is being planned or carried out by key partner agencies

- prioritise evidence gaps to deliver the greatest value-add in the UK’s understanding of the threat, improving awareness of the nature, extent, and threat of various types of economic crime

Whilst the evidence base for a broad range of economic crime types (money laundering, fraud, corruption, market abuse and sanctions evasion) were reviewed, this research strategy focuses on two priority areas: fraud and money laundering[footnote 2].

This document is designed to help external partners considering research in economic crime to focus their work on the priorities most important to the Government. This will help to improve the evidence base on which policy choices are made and target resources on the most important risks and vulnerabilities.

The role of partners in supporting the Government in the fight against economic crime is vital, and we look forward to developing this work with you.

2. Summary

This document summarises research priorities to support the current (as at February 2021) and future needs of the Government’s Economic Crime Plan. By identifying evidence gaps and priorities, the strategy aims to set out clearly the most important areas for research and analysis in economic crime, improving the evidence base on which policy choices are made and the targeting of resources.

The research priorities have been identified in discussion with a range of stakeholders and relate specifically to the priorities set out in the Economic Crime Plan. This is to ensure that research is focused on the questions most relevant to current policy priorities that will have the greatest impact. Overall, the strategy made the following conclusions:

- a wealth of information is currently held on economic crime and more can jointly be done to improve the evidence base through both primary and secondary research

- our understanding of the threat from economic crime is generally poor, though some areas have stronger evidence than others

- there are cross-cutting gaps in evidence across the economic crime types

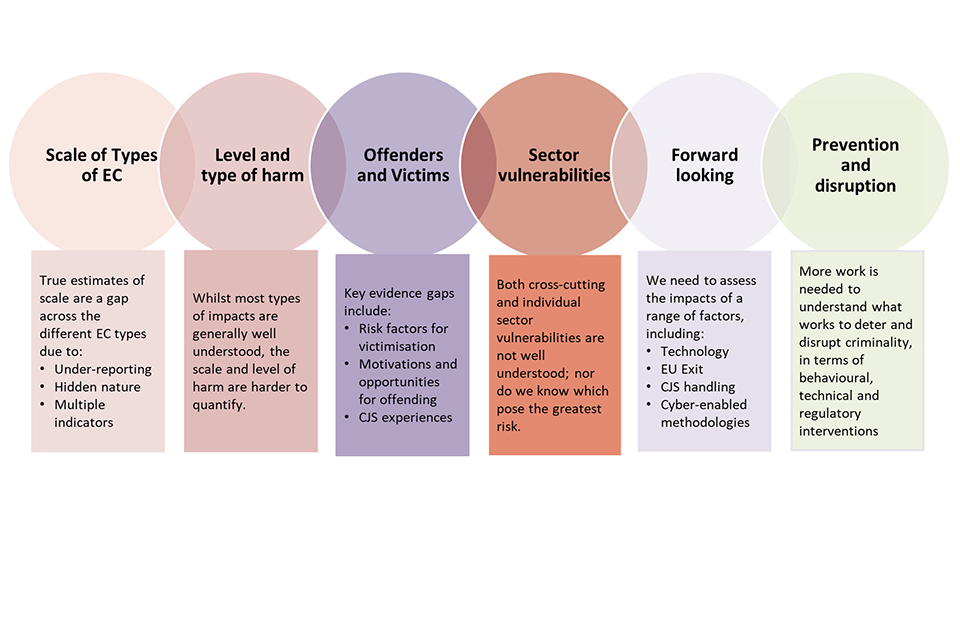

The most common evidence gaps found across all of the crime types examined are outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Cross-cutting evidence gaps

Scale of Types of EC

True estimates of scale are a gap across the different EC types due to:

- under-reporting

- hidden nature

- multiple indicators

Level and type of harm

Whilst most types of impacts are generally well understood, the scale and level of harm are harder to quantify.

Offenders and Victims

Key evidence gaps include:

- risk factors for victimisation

- motivations and opportunities for offending

- CJS experiences

Sector vulnerabilities

Both cross-cutting and individual sector vulnerabilities are not well understood; nor do we know which pose the greatest risk.

Forward looking

We need to assess the impacts of a range of factors, including:

- technology

- EU exit

- CJS handling

- Cyber-enabled methodologies

Prevention and disruption

More work is needed to understand what works to deter and disrupt criminality, in terms of behavioural, technical and regulatory interventions.

There is value in addressing all of these evidence gaps, but for the purposes of focusing this strategy on the priorities most relevant to delivery of the Economic Crime Plan, the remainder of this document focuses on a smaller number of specific research areas and crime types: the agreed national strategic economic crime priorities, fraud and money laundering.

The Government is committed to working collaboratively with the wider research community to improve the evidence base on economic crime. Therefore, we include contact details for Home Office analysts working in this area.

3. Background

Economic crime represents a significant threat to the UK that is ever-changing and evolving. Frequently, economic crime is serious and organised. Criminality flourishes when organised criminals can launder the proceeds of their illicit activity.

Money laundering in the UK represents the illicit proceeds of a range of serious crimes including large-scale drug dealing and human trafficking. The Office for National Statistics estimated there were 4.4 million fraud offences in England and Wales in the year ending September 2020[footnote 3] alone. Terrorism can be financed through funds collected both unlawfully and lawfully. Whilst the raising and moving of funds is not a terrorist’s primary aim, it may be an important enabler. Despite ongoing work, gaps remain in the UK’s current collective understanding of the threat of economic crime.

While there is not a wholly reliable estimate of the total scale of economic crime, all assessments within the public and private sectors indicate that the scale of the economic crime threat continues to grow.

The estimated volume of fraud against individuals is high, representing approximately a third of all estimated crime occurring in England and Wales. These figures only represent part of the picture as there is no reliable estimate for the volume of fraud against businesses. No reliable estimate exists for the scale of money laundering impacting the UK annually – but it is likely to be tens of billions of pounds.

Cash-based money laundering, including through the use of money mules and money service businesses, remains a significant threat. Substantial funds are also laundered via capital markets and through trade-based money laundering, reflecting the use of complex financial systems, professional enablers and insiders for high-end money laundering. Misuse of crypto-assets and alternative banking platforms are also being used to obscure ownership of assets.

The Economic Crime Plan, published in July 2019, reflects the continued and growing threat posed by economic crime. Action 5[footnote 4] of the Economic Crime Plan states the commitment to “resolve evidence gaps through a long-term research strategy”. The Home Office, working with the National Economic Crime Centre (NECC), HM Treasury (HMT) and other key partners, has led on this action.

Action 5: Resolve evidence gaps through a long-term research strategy

2.14 An important part of building our capacity to respond is improving our evidence base. Good quality and robust research is fundamental to ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the threat and the most effective and efficient targeting of resources. To this end, the Home Office, working with the NECC and other key partners, will produce a long-term research strategy by December 2019, setting out the key evidence gaps in our understanding of the threat from economic crime.

2.15 This long-term research strategy will seek to map existing work that is being planned or carried out by key partner agencies; prioritise evidence gaps which will deliver the greatest value-add in our understanding of the threat; and, will focus on improving our awareness of the nature, extent, and threat of various types of economic crime. Developing the evidence base cannot be achieved by government or law enforcement alone. We will work with partners from academia, industry and elsewhere to tackle the research questions that most clearly support implementation of this action.

2.16 The strategy will include policy work, led by the Home Office in conjunction with HM Treasury and the Ministry of Justice, to review whether the statistics that are collected on economic crime, particularly criminal justice statistics, can be improved. This should consider the FATF MER’s recommendations on the collection of statistics under the UK’s AML CTF regime and the UNCAC review’s recommendation on developing a better understanding of the threat posed by domestic corruption.

There are significant gaps in the evidence base on economic crime. Some of these will be addressed via threat and risk assessments, including:

- the National Crime Agency’s (NCA’s) National Strategic Assessment (NSA), which assesses the economic crime threats facing the UK on an annual basis

- a HMT-led national risk assessment (NRA) of money laundering and terrorist financing[footnote 5], which provides an overview of the risks and likelihood of a criminal activity occurring

This research strategy builds on these assessments, providing a clear, current and prioritised set of research needs relating to the 2019 Economic Crime Plan from a range of stakeholders. The intention is that this research strategy will set the direction for both internal government research and that of the external research community to improve the evidence base on economic crime.

3.1 Focusing evidence needs on the Economic Crime Plan

The Economic Crime Plan sets out seven priority areas for combatting economic crime. These reflect the greatest barriers to combatting economic crime and where we see the most scope for collaborative work between the public and private sectors to improve our response. Each of these elements are inter-related and the reform of each will improve and strengthen our overall system response to economic crime.

Strategic priorities

Develop a better understanding of the threat posed by economic crime and our performance in combatting economic crime.

Pursue better sharing and usage of information to combat economic crime within and between the public and private sectors across all participants.

Ensure the powers, procedures and tools of law enforcement, the justice system and the private sector are as effective as possible.

Strengthen the capabilities of law enforcement, the justice system and private sector to detect, deter and disrupt economic crime.

Build greater resilience lo economic crime by enhancing the management of economic crime risk in the private sector and the risk-based approach to supervision.

Improve our systems for transparency of ownership of legal entities and legal arrangements.

Deliver an ambitious international strategy to enhance security, prosperity and the UK’s global influence.

A sound evidence base in all these areas is essential, but research is hindered by the complex nature of economic crime. The clandestine nature of most economic crimes presents challenges in developing an effective response. Economic crimes can involve complex methodologies that are continuously changing as criminals and terrorists identify and exploit new vulnerabilities in society. Therefore, we need to maintain a comprehensive and up-to-date understanding of the threat.

There is no single definition on which to base research questions. This research strategy follows the same definition as the Economic Crime Plan: Economic crime refers to a broad category of activity involving money, finance or assets, the purpose of which is to unlawfully obtain a profit or advantage for the perpetrator or cause loss to others. It includes criminal activity that:

- allows criminals to benefit from the proceeds of their crimes or fund further criminality

- damages the UK’s financial system and harms the interests of legitimate business

- undermines the integrity of the UK’s position as an international financial centre

- poses a risk to the UK’s prosperity, national security and reputation

The main categories of economic crime covered plan are: fraud; terrorist financing; sanctions contravention; market abuse; corruption and bribery; and the laundering of the proceeds of all crimes. It also includes asset recovery (criminal and terrorist). While we initially focused on the full list of economic crime types, following stakeholder consultations, the research strategy focused on a smaller number of priority areas: fraud and money laundering. The Home Office will publish separately priority research areas for corruption and bribery.

The complexity and challenges of this research area means that there are many evidence gaps, ranging from broad thematic questions to very specific criminality-focused gaps. A key feature of this document is that it relates evidence needs directly to the priorities set out in the Economic Crime Plan.

3.2 Methodology

The evidence base on which this strategy was developed includes a range of data, information and research on economic crime. These include: research by government, academics or other agencies; management information; primary or secondary data collection; law enforcement intelligence; and risk assessments.

The development of this research strategy was an iterative process, involving a range of stakeholders from within and outside Government and included the following activities:

- stakeholder mapping exercise to identify possible agencies holding information on economic crime

- data collection exercise to understand what information is held

- review of academic literature

- thematic analysis to identify both cross-cutting and crime type specific evidence gaps

- prioritisation of key knowledge gaps

The relative priority of the identified evidence gaps was assessed according to the following criteria:

- gaps most relevant to the implementation of the 2019 Economic Crime Plan

- gaps relating to the greatest threats

- areas where there is no, or limited, existing research

The final set of priorities were agreed through continued stakeholder consultation, including an expert workshop to refine the research questions and discuss methodological approaches and academic capabilities for economic crime research.

3.3 Building a stronger research community

In the same way the threat from economic crime cannot be solved by government and law enforcement alone, the research priorities outlined in this document require a broad community of researchers and analysts to focus on where more evidence is needed.

The publication of this research strategy is a step-change in facilitating a discussion about research in this area, bringing opportunities for diverse partnerships and collaborations between specialists and across sectors. By adopting this approach, we anticipate further widening various ideas and skills, and highlighting different issues, problems and solutions. Contributions from a variety of stakeholders offers the opportunity for more rigorous and effective research and we are committed to encouraging discussion. Interested parties can contact Home Office analysts via the dedicated email address: SOCResearchAgenda@homeoffice.gov.uk. Home Office statistical and research reports can be found on the Home Office publications website[footnote 6].

4. Thematic research areas

Six key thematic areas were identified for further research. These were identified after reviewing the evidence for each type of economic crime and analysing the key gaps.

- Scale of economic crime: The extent of a crime in terms of estimates of the number of offences.

- Level and type of harm: The impacts of economic crime, including costs.

- Offenders and victims: The nature of offending, offenders, methods and victims.

- Sector vulnerabilities: The enablers or drivers of economic crime, for example, industries, services or products.

- Forward looking: The trends over time and the impacts of social, economic and technological change.

- Prevention and disruption: The factors or interventions that work to disrupt or deter criminal activity.

This research strategy presents evidence gaps thematically and for fraud and money laundering. Only research areas that were assessed as the highest priority are included within this section, meaning that some of the thematic areas outlined above do not feature.

The priority areas described are not intended to specify the exact research questions researchers should focus on but are instead designed to set the scene for future research. We would encourage researchers to collaborate and innovate to develop more specific research questions in these areas.

4.1 Priority research areas

This section describes priority research areas in four thematic areas. However, there is considerable overlap between the themes and within and across the different types of economic crime, as well as to the priorities outlined in the Economic Crime Plan.

We would encourage researchers to consider all priority research areas when planning research in their own area of expertise rather than viewing them in isolation. A number of the evidence gaps identified are very similar for both fraud and money laundering, and comparative research by offending and offence type would offer significant value. For all areas, consideration should be given to how information held by separate organisations can be used to better target and mitigate economic crime threats.

4.2 Understanding offenders and offending

Evidence gaps relating to the perpetrators of economic crime were highlighted as key priorities for informing how we prevent criminality and protect those at risk of victimisation. The priority research questions identified in this area are outlined in List 1.

List 1: Priority research questions – Understanding offenders and offending

Crime type: Fraud and money laundering

Research area: Offender pathways and decision making

Description: Knowledge of offenders, who they are, how they come to be involved in offending and how they commit offences, remain a key gap in our understanding. Whilst we have a relatively good understanding of offender motivations, the routes by which they become involved in economic crime, as well as their links to serious and organised crime, are less well researched. It is also unclear what drives desistance amongst these offender groups and the roles and types of professionals involved are hard to identify.

Research to build the evidence base in these areas will need to focus on the varying types of fraud and money laundering and consider the full diversity of offending, including those emerging in recent years.

Understanding how offending may vary according to the target victim population, opportunity and situational context or environment, and for money laundering, predicate crime type, is also important for informing potential intervention options.

Crime type: Fraud

Research area: Links with other types of criminality

Description: Fraudsters use a range of methods, which they can adapt and develop quickly and can even change during interactions with victims. Money laundering is intrinsically linked with fraud and a variety of other crime types. More research is needed to understand the wider links of fraud with other types of crime and to understand how disruption in one area could help impact on other forms of economic crime.

Fraud is not a new crime but it has evolved with the rise in technology and the internet. Cyber-criminality is a key enabler of fraud. Over half of estimated fraud offences in the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) have an online aspect[footnote 7]. However, the full picture of how cyber-crime contributes to, and interacts with, fraud is not clear, specifically how the Computer Misuse Act 1990 offences facilitate fraud and other crime types, including terrorist financing. This is a significant evidence gap.

Crime type: Money laundering

Research area: Money laundering networks

Description: The UK has a large, open financial sector, which leaves it vulnerable in several ways to money laundering. Combined with other high-risk factors, the UK is an attractive place for criminals to hide their illicit gains. These risks often interact and can be exploited together, heightening the risk of money laundering.

We have a good understanding of the enablers of and risk factors for money laundering. However, there is less information on the nature of the ties to serious and organised crime groups and the extent to which networks operate and are interlinked, both within and outside the UK

4.3 Sector vulnerabilities

The risks of victimisation for businesses are not well understood and it is not clear which factors pose the greatest threat. Previous research and analysis have tended to focus on single sectors. The priority research questions identified in this area are outlined in List 2.

List 2: Priority research questions – Sector vulnerabilities

Crime type: Fraud and money laundering

Research area: Systematic assessment of vulnerabilities across and between sectors

Detail: Whilst the sector vulnerabilities for some types of fraud and money laundering are well understood, for others the evidence base is weak.

Priority work in this area should focus on building the evidence base within sectors, by type of offence (for money laundering, by predicate crime type) and by domestic and international factors.

A systematic review of evidence should be undertaken to assess the commonalities and differences across and between sectors.

4.4. Forward looking

With the continuing evolution of serious and organised crime, economic crime is becoming more sophisticated and complex. Fraud methodologies adapt and change to exploit enablers such as social engineering, ID theft and cyber technology. Methods to disguise illicit flows have become increasingly complex and new technologies, like virtual currencies, are an increasing threat. The priority research questions identified in this area are outlined in List 3.

List 3: Priority research questions – Forward looking

Crime type: Fraud and money laundering

Research area: How will the threat evolve and what are the future threats?

Description: Criminals are adept at exploiting opportunities to further their profit. New methodologies for offending are responsive to change and more research is needed to fully understand the impacts on offending.

Technological change is a significant factor, but other factors, such as EU exit, cyber-enabled methodologies, the impact of COVID-19 on offending and the criminal justice handling of economic crime should also be considered.

4.5 Prevention and disruption

In order to deter and disrupt criminality, we need to ensure that the powers, procedures and tools in place are as effective as possible. A better understanding of what works will mean our efforts are targeted and will inform future investment and operational decisions. The priority research questions identified in this area are outlined in List 4.

List 4: Priority research questions – Prevention and disruption

Crime type: Fraud and money laundering

Research area: ‘What works’ in the prevention and disruption of economic crime?

Description: An improved understanding of what works for combatting economic crime was identified as a priority evidence gap across the board.

Research should focus on behavioural, technical and regulatory interventions and consider how information and data could be better used to inform the response. Research to understand how investigation into economic crime could be improved was also highlighted as important. Research into protective factors or behaviours should also be undertaken to help to identify strategies for reducing the risk of victimisation.

Consideration should be given to the effectiveness of interventions, but also wider factors such as value for money; the environment must be made as difficult as possible for criminals, while allowing businesses and individuals to prosper.

5. Conclusions and implications for policy and research

This research strategy has been published to communicate analytical priorities for economic crime and to encourage wider research by academics and other research agencies. It provides a high-level overview of key evidence gaps and should be viewed in conjunction with other data sources, such as official statistics, the National Risk Assessment for money laundering and academic research.

We invite academics and researchers to contact Home Office analysts via the dedicated email address provided in this document to discuss their planned research and how this might have the greatest strategic and operational impacts. At the same time, government departments, operational partners and associated bodies with responsibility for economic crime should plan their analytical activities with these priorities in mind.

We will work with the UK Research Councils to maximise dissemination of this agenda and to help to inform the prioritisation of future funding for research. Whilst the focus of this document has been on identifying key gaps in our knowledge, the wider aim of publishing this list of priorities is to improve communication and collaboration between partners and enable better dissemination and application of research to support strategic and operational decision making. Economic crime presents a challenging research area, and robust, relevant evidence is crucial for ensuring that our response is as effective as it can be, both now and in the future.

In the same way that the threat from economic crime cannot be solved by law enforcement alone, the research priorities outlined in this document require a broad community of researchers and analysts to help to identify and address areas where more evidence is needed. The publication of this research strategy brings opportunities for a diverse range of partnerships and collaborations, both between specialists and across sectors. We encourage a range of contributions from different stakeholders employing a range of methodologies and considering social, economic, behavioural, computer science and business approaches to provide us with the highest quality evidence.

6. The research landscape

There are a number of existing bodies with expertise in economic crime research, each playing an important role in building evidence in this area. This section contains useful information and contact details for existing centres of expertise for economic crime research, as well as potential funding sources (otherwise, funding is not within the scope of this document). It is by no means exhaustive but covers some of the main UK and international organisations in this area.

6.1 Networks

Networks: National Economic Crime Centre (NECC)

Detail: The NECC, hosted within the National Crime Agency (NCA), was established in 2018 and leads and coordinates the UK’s response to economic crime both at home and abroad that has a national impact. The multi-agency initiative comprises representatives from a variety of law enforcement and government departments, who work together to progress national and departmental priorities on economic crime. They do so by harnessing intelligence and capabilities from across the public and private sectors to tackle economic crime in the most effective way. It works with partners to jointly identify and prioritise the most appropriate type of investigations, whether criminal, civil or regulatory, to ensure maximum impact.

Networks: Centre for Financial Crime and Security Studies (CFCS): Royal United Services Institute (RUSI)

Detail: The CFCS is a research-led partner for policymakers and private sector actors seeking to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of current approaches to tackling money laundering and terrorist financing in the UK and globally.

Networks: European Financial and Economic Crime Centre (EFECC)

Detail: The EFECC enhances the operational support provided to the EU Member States and EU bodies in the fields of financial and economic crime and promotes the systematic use of financial investigations.

Networks: Joint Money Laundering Intelligence Taskforce (JMLIT)

Detail: A partnership between law enforcement and the financial sector to exchange and analyse information relating to money laundering and wider economic threats. JMLIT provides a mechanism for law enforcement and the financial sector to share information and work more closely together to detect, prevent and disrupt money laundering and wider economic crime.

Networks: UK Finance

Detail: Representing more than 250 firms UK Finance promotes a safe, transparent and innovative banking and finance industry, offering research and policy expertise.

6.2 Academic institutions

Academic institutions: University of Portsmouth Centre for Counter Fraud Studies (CCFS)

Detail: The CCFS offers research and knowledge services to publicise and explain the problems of fraud and economic crime.

Academic institutions: The Financial Crime Compliance Research Interest Group (FCC RIG)

Detail: The FCC RIG brings together academics, lawyers and financial services professionals with a view to: producing research outputs; designing and implementing teaching materials; providing and hosting seminars, conferences and workshops; designing and providing tailored FCC awareness training consistent with stakeholder needs; and encouraging international collaboration.

Academic institutions: Institute of Advanced Legal Studies

Detail: A national academic institution, attached to the University of London, serving all universities through its national legal research library to promote, facilitate and disseminate the results of advanced study and research in the discipline of law, for the benefit of persons and institutions in the UK and abroad.

Academic institutions: The Centre for Financial and Corporate Integrity (CFCI)

Detail: The CFCI aims to create an awareness and understanding of the complex inter-relationships between economics, finance, accounting and law.

Academic institutions: Academic Centres of Excellence in Cyber Security Research (ACEs-CSR)

Detail: The ACEs-CSR is an initiative outlined in the national cyber security strategy Protecting and Promoting the UK in a Digital World. All universities that meet the criteria are invited to join the scheme.

Academic institutions: Cambridge International Symposium on Economic Crime

Detail: Organised by some of the world’s leading educational and research institutions with the involvement of numerous governmental agencies, the judiciary, the professions, compliance bodies, and the business world. It provides a forum for the practical analysis and discussion of the real threats facing our world as a result of criminal and subversive activity. Its primary objective is to promote meaningful cooperation in the prevention and control of economically motivated crime and misconduct.

Academic institutions: Financial Crime and Cyber Crime Research Network

Detail: The Financial Crime and Cyber Crime Research Network comprises members of the Global Crime, Justice and Security Research Group, the Computer Science Research Centre at the University of the West of England (UWE) Bristol, and external scholars.

6.3 Global institutions

Global institutions: European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR)

Detail: The ECPR’s Standing Group on Organised Crime (SGOC) promotes research across disciplinary, regional and professional boundaries.

Global institutions: Transparency International (TI)

Detail: TI is the UK’s leading independent anti-corruption organisation. For more than 25 years TI has worked to expose and prevent corruption so that no one in the UK and where the UK has influence has to suffer its consequences.

Global institutions: Global Initiative against Transnational Organised Crime

Detail: Based in Geneva, the Global Initiative comprises a network of nearly 300 independent global experts working on human rights, development and, increasingly, organised crime.

Global institutions: Financial Action Task Force (FATF)

Detail: The global money laundering and terrorist financing inter-governmental watchdog. Sets international standards that aim to prevent these illegal activities and the harm they cause to society.

The FATF works to generate the necessary political will to bring about national legislative and regulatory reforms in these areas. With more than 200 countries and jurisdictions committed to implementing them, the FATF has developed the FATF Recommendations or FATF Standards, ensuring a co-ordinated global response to prevent organised crime, corruption and terrorism.

The FATF monitors countries to ensure that they implement the FATF Standards fully and effectively and holds countries that do not comply to account.

6.4 Government and law enforcement

Government and law enforcement: Europol

Detail: Europol is the EU’s law enforcement agency, specialising in strategic and operational intelligence analysis in the fight against organised crime and terrorism.

Government and law enforcement: Action Fraud

Detail: The UK’s national reporting centre for fraud and cyber-crime. This is where victims should report fraud if they have been scammed, defrauded or have experienced cyber-crime in England, Wales or Northern Ireland.

Government and law enforcement: Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU)

Detail: Core functions include the receipt, analysis and transmitting of reports of suspicions identified and filed by the private sector. The added value of the FIU is the analysis it undertakes of all the information received, as well as the broad range of other financial information it has at its disposal and which it can use to better assess the information on suspicions provided.

Government and law enforcement: National Crime Agency (NCA)

Detail: The NCA is an intelligence-led agency driven by a central intelligence hub. The NCA’s National Strategic Assessment provides a single picture of the threat to the UK from serious and organised crime.

Government and law enforcement: Joint Fraud Taskforce (JFT)

Detail: The JFT was set up in 2016, to work with the private sector, law enforcement and the Government to protect the public from fraud.

Government and law enforcement: Legal Sector Affinity Group (LSAG)

Detail: The LSAG is a meeting of all the UK’s legal professional body Anti-Money Laundering Counter Terrorism Financing (AML CTF) supervisors. It aims to support the achievement of the UK’s AML CTF regime through the development of guidance, sharing of best practices, input to national developments and liaison with the Government.

Government and law enforcement: National Fraud Intelligence Bureau (NFIB)

Detail: A unit in the City of London Police, responsible for gathering and analysing intelligence relating to fraud and financially-motivated cybercrime.

Government and law enforcement: Serious Fraud Office (SFO)

Detail: A specialist law enforcement agency that investigates and prosecutes the top level of serious and complex fraud, bribery and corruption, and associated money laundering.

Government and law enforcement: Financial Conduct Authority (FCA)

Detail: The FCA regulates the financial sector and financial advisers, and pursues criminal prosecutions, including for market manipulation. It is also an Anti-Money Laundering Counter Terrorism Financing supervisor for financial institutions.

Government and law enforcement: Fraud advisory panel

Detail: Comprises members from all sectors – public, private and voluntary – and many different professions united by a common concern about fraud and a determination to do something about it. The panel champions best practice in fraud prevention, detection, investigation and prosecution, and helps people and organisations to protect themselves against fraud.

6.5 Other centres of expertise

Other centres of expertise: What Works Centre (WWC) for Crime Reduction: College of Policing

Detail: The focus of the WWC for Crime Reduction is on practices and interventions to reduce crime. The WWC is also involved in other related areas, such as local economic growth, early intervention and wellbeing.

Other centres of expertise: The Police Foundation

Detail: The Police Foundation is a think tank representing the only independent body in the UK that researches and works to improve policing for the benefit of the public through an impartial perspective.

Other centres of expertise: Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats (CREST)

Detail: CREST is a national hub for understanding, countering and mitigating security threats. It has a plan for sustained and long-term growth, through stakeholder and international researcher engagement.

Other centres of expertise: RAND Corporation

Detail: RAND Europe is a not for profit research institute, involved in areas including security, health and education. Much of this research is carried out on behalf of public and private grantors and clients.

Other centres of expertise: Centre for Counter Fraud Studies (CCFS)

Detail: The CCFS is one of the specialist research centres of the Institute of Criminal Justice Studies. The Centre provides a central knowledge resource, and aims to identify areas for future research.

-

Not including proceed generating crimes, such as drug or human trafficking. ↩

-

Although this figure is not directly comparable with previous estimates due to a change in methodology, the estimate for fraud lies within the range of those reported in recent years. (Crime Survey for England and Wales, 2020). ↩

-

Action 2.16 is not included within the scope of this document. ↩

-

National risk assessment of money laundering and terrorist financing 2020. ↩

-

For official statistics, for research reports. ↩

-

An estimated 53% of fraud offences in England and Wales were cyber-related in the year ending March 2020 (CSEW). ‘Cyber-related’ refers to where the internet or any other kind of online activity was involved in the commission of the offence. ↩